Anton Krupicka - Gore Range Traverse Attempt

This kind of traverse, 40mi with 18-20k’ of vert, was exactly why I’d become interested in the sport...

- - -

When I started skiing three years ago, my intent was always to use it as a means to travel untrammeled through the mountains.

Not to only run repeats on the local resort’s groomer treadmill.

Not to only train for and race in sanctioned skimo events.

Not even to just rack up powder laps at the local backcountry stash (though that’s pretty nice).

No, I wanted to use skis to pursue the same endeavors I enjoy in the summer—multi-peak link-ups; long, alpine traverses—but in the winter, when the mountains, blanketed in snow, demand more than just running or climbing shoes.

Backcountry Learning Curve

Last season, finally starting to feel confident enough on the steeps in skimo races, marked the beginning of my (minor) forays into what might be termed proper ski mountaineering: climbing and skiing mountains by steep (-ish), (semi-) technical routes.

Almost immediately, I was dealt a more-than-rude wake-up call to the reality of the seriousness of this activity. Mid-March of 2017: I joined my buddy Jason Killgore on a dawn patrol mission to Rocky Mountain National Park to climb and ski the Tyndall Gorge classic—Dragon’s Tail couloir. After booting up, we were forced to change plans as a stubborn cloud was preventing the icy snow from softening. We headed over to a more northern aspect, the Ptarmigan Headwall but this too proved to be near rock-hard windboard, though slightly less steep. Still, we started down.

Conditions like this offer no margin for gumbie maneuvers, and when I flubbed a turn I immediately found myself rocketing down the 800’ length of the face, losing all skis, poles, gloves, and my axe. My GPS watch would record my top speed at 33mph. I got exceedingly lucky and only had to kick one rock—but this broke my boot and resulted in a deep bone bruise in my left heel, hampering foot travel for a few weeks afterwards. I was subsequently very wary—and acutely aware of the stakes of high consequence terrain—but managed a couple more days of steeper skiing before the season’s end.

"My GPS watch would record my top speed at 33mph."

This year, my first priority was to begin my education in earnest. I spent as many days as possible backcountry skiing with friends, gaining experience in variable snow conditions on big mountains, and evaluating snow stability in variable conditions.

The Gore Range

A couple months ago, when Jason and Chris Baldwin shared with me their plan to traverse the entire Gore Range (just north of Silverthorne), I was immediately on board. The Gores are an unsung gem of Colorado (no 14ers to attract the masses) that get substantial snow and have east-west oriented ridges extending off the roughly north-south trending range crest. Additionally, it’s exceptionally beautiful with innumerable craggy ridgelines strung together, as opposed to the talus piles that seem to compose most of Colorado’s alpine terrain.

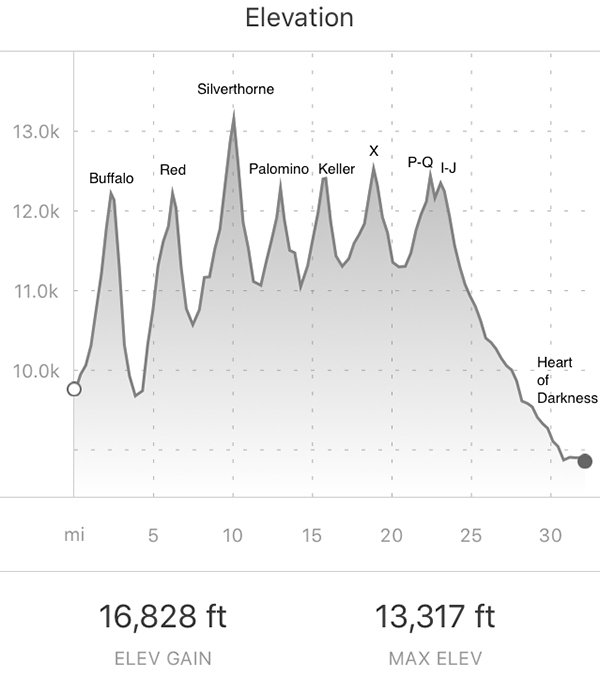

Objective: Start in Silverthorne with Buffalo Mountain and head north just east of the range’s spine, climb up then ski down each alpine ridge until we reached the final high point—Eagle’s Nest—at the range’s north end. This kind of objective was exactly why I’d become interested in the sport— a total distance ranging from 35 to 40mi accompanied by a burly 18-20k’ of vert.

Gore Range Elevation Profile

Jason and Chris are much more skilled and experienced skiers than I. Jason and I race the full skimo season in Colorado, so I knew firsthand that he at least matches me on the uphills. Chris, a former professional cyclist (two-time National Time Trial Champion, though he’d never tell you) has in recent years applied that same fitness, intensity, and passion to ski mountaineering. I’ve never seen him tired, or even unenthusiastic. He’d attempted this traverse from the west side the previous year, but came up a few ridges short.

When Jason and Chris cited the extra safety factor of having three people instead of just two, I knew the reality was that these guys would be making most (if not all) the navigation decisions and opening every run. I was just a noob trying to keep up while trying to soak up as much knowledge as possible

A Midnight Start

April 26th: After leaving a car at our hoped-for finishing point (the north end of Green Mt Reservoir), we left the Buffalo Mt trailhead at 12:11am with basically no sleep. No matter, with the balmy nighttime temps and bright moon our collective stoke was pegged out on the nearly 3000’ climb to the top of the classic Silver Couloir (12,500’). As a designated North American 50 Classic ski descent, the Silver is on many skiers’ tick-lists. Partly due to this popularity, it would end up being the worst run of the whole traverse—punchy, icy, and pretty skied out—my focus was on maintaining control in the dark and just getting down in one piece.

A bit of bushwhacking and route-finding at the bottom led us over to the next peak—“East East Red”—and another nearly 3k’ ascent to 12,500’.

Yes! Our whoops of delight rang through the night as we descended the northeast gully’s amazing, moonlit powder. It was still very early, energy was high, and the skiing was excellent. At the bottom, we knew was one of our only chances for refilling water—we’d each started with a hefty 4L—so we took our first real break directly on top of the stream to eat breakfast.

Sunrise Woes

About 500’ up another 3k’ climb to Silverthorne Peak, the sun began rising and we paused to don sunglasses and sunscreen. Except Jason couldn’t find his sunglasses. This was nontrivial. On a bright, sunny day in a world of snow, eye protection is basically mandatory. Snow-blindness is a real thing. There was even talk of bailing, but we decided to keep trucking until the issue became more critical and we were forced to examine other options.

Jason and Chris skinning towards Silverthorne Peak at dawn.

Our solution: rotating our two sets of sunglasses across three pairs of eyes. Later in the day, as the intensity of the sun peaked, the third person was forced to skin uphill with a Buff pulled fully over his face, the cheesecloth fabric providing just enough visibility to keep skinning, and sweet relief from the blinding brightness.

Putting on crampons for the traverse over to our descent off Silverthorne.

Silverthorne Peak was the first unknown of the day. We hadn’t heard of anyone skiing north off of it, and doing so from the summit didn’t look particularly promising on topo maps. To avoid some cliffs and get down to what we hoped was a skiable couloir, we had to first drop a bit to the southwest. Since it was still just after sunrise, these southern aspects at 13,300’ were steep and frozen solid. Not worth the risk. We all donned crampons and employed axes to downclimb and then traverse over to our col. Much to our delight, north couloirs were consistently skiing just as we’d hoped—some variability and a couple windslabs to mind, but overall offering legit, soft powder on each run.

Chris downclimbs the frozen upper slopes of Silverthorne Peak.

I was already tired on the climb up to Silverthorne—the sleepless night catching up perhaps? With 8500’ of vert already logged, the next three ridges (Palomino, Keller, and X) were a blur of uphill slogs, followed by descents with surprisingly good snow. Compounding fatigue notwithstanding, stoke remained high. We were all just grateful to be undertaking such a big adventure in a beautiful place with favorable conditions.

Engineering An Exit

But the day was getting long. After the descent off X, the next climb up to the P-Q col seemed never-ending—I was pooped. With no cover, the afternoon sun beat was relentless and the upper valley felt so vast that our progress beneath the toothy ridge felt almost imperceptible. Onsight skiing off of Mt Powell (the highest in the range at 13,500’) and Eagles Nest (the last ridge) in darkness was a non-option, so before the final headwall zig-zag up to the pass, we paused in the shade of the ridge (shadows lengthening, time inexorably running out), contemplating various exit strategies.

Downclimbing into our descent couloir off the Palomino Ridge.

Tuck our tails, grunt over the range divide, and descend southwesterly to Vail? Tag the next two ridges, descend the Black Creek drainage, and salvage our goal of a full traverse with a game tag of Dora Mt (known terrain and part of the final ridge, but skipping the 1,000’ higher, prouder summits of Powell/Eagle’s Nest) before exiting to our car? Jason and Chris had resolve; I basically did whatever they told me to—we decided to traverse two more ridges, then keep pushing on to Dora.

Chris enjoying some afternoon powder turns.

While the descent from P-Q was only about 500’, it was succeeded by a soul-crushing bootpack in unsupportive mashed potatoes to gain the I-J col (12,600’), the last obstacle before the descent down the Black Creek drainage. We made it here a bit after 5pm; looking down the valley, there seemed to be a nice slide path to ascend the flanks of Dora at the end of the final ridge. Maybe we’d top out in the dark, but the descent of the other side would be a known 25-degree powder field, easy in the dark. Home stretch!

Jason descends from the corniced P-Q col.

For a while, things went to plan. An epic final schuss through mellow slopes of heroic corn and then coasting down to treeline had our spirits high. Upon entering the trees, the terrain flattened out, and, in retrospect, a completely different—and brutally extended—chapter of the outing began.

The Bushwhack From Hell

At first, travel took on that of the typical spring skiing exit—boots locked, skis skinless, skate a bit here, duck through some branches there, gumby over the occasional fallen tree, awkwardly herringbone and tin-man march when needed. This worked for a while. But then it kept going. And going. All three of us were exhausted and the tedious travel gradually wore us down as the sun dipped behind the mountains and the light dimmed. But what to do? Keep plugging.

Bushwhacking is never fun. Even less so with skis attached to your feet after nearly continuous movement for 20 hours. We constantly tried to anticipate which side of the creek would offer the quickest passage and tried not to fall in the water. Not easy.

Dora seemed to get no closer. Exhaustion dulled crucial motor skills and coordination. It soon became obvious that the hoped-for slide path ascending Dora was mostly without snow (south-facing) and, in fact, was a complicated puzzle of undergrowth and cliffs. It didn’t matter: we weren’t even to the base yet. We revised our objective again; let’s just get to Black Lake. Our map told us that on its far, east end was a private road that we could take a few miles out to the Green Mt Reservoir Rd, where maybe we could hitch a ride back to our car.

"Dora seemed to get no closer. Exhaustion dulled crucial motor skills and coordination."

Descent Into Darkness

Except that Black Lake wasn’t getting any closer either. At one point, we followed a set of frying pan-sized bear tracks down what was surely a cascade in the summertime. Maybe Bear knew where the hell he was going; we were getting pretty frazzled and bordering on desperate.

Inevitably, darkness settled. Headlamps on, stay psyched! After more than two hours of ‘schwacking, we finally donned skins and continued picking our way through the jungle-scape, trying to divine the quickest, clearest passage down-drainage.

At one point we became cliffed-out on our side of the creek (not before I’d managed to tumble head-over-heels down a not-minor scarp, skis still attached) and decided that crossing it was the only option. Jason and Chris both filled their boots with creekwater after punching through snow. We shimmied over on a log, throwing our skis and poles across the waterway. In the dark. Fun stuff. Suffice it to say, it was grueling. Right around midnight, SIX HOURS of bushwhacking later, we reached the western shores of Black Lake. Hallelujah!

"Jason and Chris both filled their boots with creekwater after punching through snow."

Except the lake wasn’t frozen enough to ski across. At the moment of this realization, the group’s deflation was palpable. All a bit bewildered about what to do, we just took a minute to sit. I wondered why I was slurring my speech, then realized that I’d been awake for 42 hours and skiing for 24 hour. Chris laid down directly on a comfy patch of lake ice, not even sitting on his pack. Nice spot for a bivy. During the following two extra hours of bushwhacking it took to reach the eastern end of the lake, if we paused for more than 10 seconds, I would immediately lay down in my tracks and doze off.

Finally (FINALLY!), we reached a double-track and then an actual gravel road. On the map, it looked about five miles from the lake to the road. In ski boots. Chris said he needed to stop and take some gravel out of his boots. No way were my boots coming off. If that happened, they weren’t going back on. While Chris emptied his boots, Jason and I laid down on the side of the road and the next thing I knew Jason was waking me up saying it was time to go. Chris had started the long march without even rousing us. In the moment, I found this to be hilarious.

The next two hours of walking were the most sleep-deprived I’ve ever been in my life. Granted, I don’t have any multi-day endurance experience, but it was pretty silly stumbling and weaving down the road under a brilliant moon, bundled in every layer, not really sure what we were going to do when, if, the road would ever end.

An Ignominious Ending

Long story short: we got there, at nearly 4am. Clearly nobody would be driving by. Chris sheepishly called the cops, who arrived in surprisingly good cheer and gave Jason a lift to his car (another few hours walk away) while Chris and I huddled on the side of the road, shivering in our emergency Bothy Bag. We all survived; after 28 hours, it never felt so good to take off ski boots.

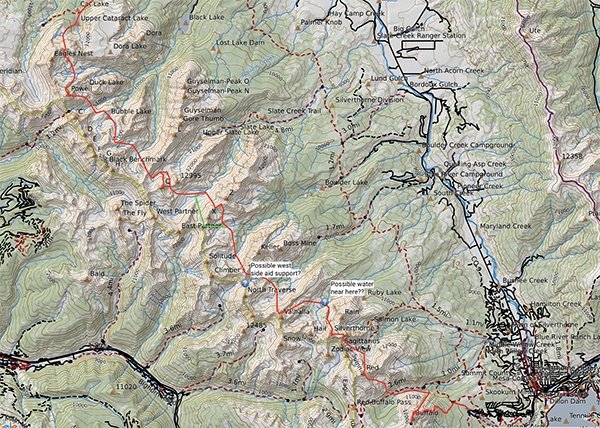

The intended route.

In the end, falling just short of our goal did little to diminish the experience. To be sure, my perception was expanded regarding the possibilities of what I could accomplish on skis, but more importantly, I came away grateful for strong and gracious partners willing to put up with my missteps along the steep curve of gaining experience in ski mountaineering. I’m looking forward to many more adventures to come.

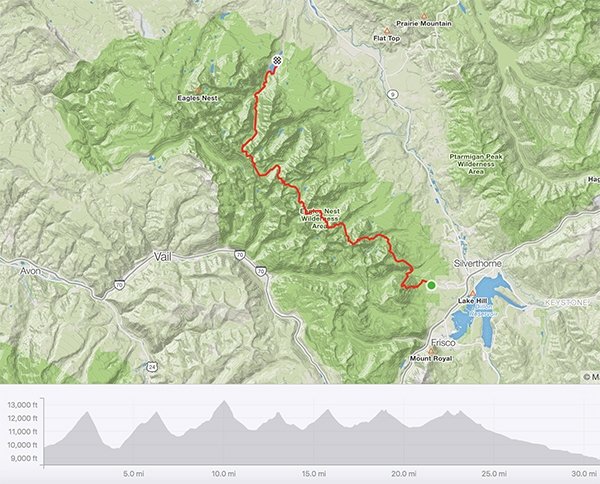

Our actual route.

Postscript: Ten days later, Chris and Jason—this time accompanied by our friend Logan—returned for the full send in 21 hours while I was happily out on a bikepacking trip in the desert. One of my feet was still bruised from our ski-booted death march anyways. I typically try to avoid hackneyed, quasi-hyperbolic praise like this, but screw it: those guys are total animals.

Photos provided by Anton Krupicka.

- - -

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ANTON KRUPICKA is a member of the La Sportiva Mountain Running® Team.

ANTON KRUPICKA is a member of the La Sportiva Mountain Running® Team.

- - -