Sagebrush and Summits - Anton Krupicka

I’m a runner. Have been for more than 26 years now. I find the elemental purity of running to be its most attractive quality...

- - -

Move over the earth, on foot, in tune with your surroundings. Running is uncomplicated and endlessly adaptable to one’s surroundings. However, the application of the basics of running–unencuz the backcountry that requires stamina for long approaches and technical expertise to negotiate. Ultimately, both forms of this movement are about covering ground under your own power. Still, when distances are truly vast the human body presents some serious limitations.

Employing the bicycle, often considered mankind’s most efficient form of human transport, offers an elegant solution to these limitations. It harnesses much of the same energy and endurance that running requires but mechanically multiplies these things in such a way that covering great distances–and carrying the supplies to do so–suddenly becomes quite reasonable. Like running, keep the legs pumping and your imagination and available time are the only limits to your travels. But it’s a lot easier to keep the legs pumping longer–and day after day–on a bicycle. As such, I find the combination of these two activities–pedaling a bike and mountain running/scrambling–to be the most natural and rewarding way to move through the natural world. The act of doing it all yourself, doorstep to doorstep, is simultaneously humbling and empowering in a way that, in my experience, imparts the greatest psycho-emotional rewards.

With this thesis as a framework, in July I completed a 21 day, 2300 mile bike tour through the northern Rockies. The motivating idea for this tour was a self-powered enchainment of six of the highest and most iconic peaks scattered across this region. These half-dozen alpine outposts were generally each separated by a couple of days of high desert pedaling, hence the moniker I chose–Sagebrush & Summits. In selecting the six mountains that the mountain running portion of this trip comprised, I sought state and/or range high points. These also happened to be particularly remote and/or technical summits, typically deep in the backcountry, often with many off-trail miles:

Kings Peak in the Uinta Range (Utah’s high point, 13,528’);

Grand Teton – the Teton Range’s high point, 13,775’);

Granite Peak in the Beartooth Range (Montana’s high point, 12,807’);

Cloud Peak – the highest mountain in Wyoming’s Bighorn Range, 13,166’;

Gannett Peak in the Wind River Range, Wyoming’s high point, 13,804’; and

Longs Peak (14,255’) in Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park, the dominant peak of the northern Front Range and the high point of my backyard skyline.

In an effort at aesthetic symmetry and an adherence to some sort of vague yet compelling personal principle, I started and ended the loop at my doorstep in Boulder, CO.

My mountain running equipment for this trip was identical for each peak: La Sportiva Freccia running shorts and dedicated socks and cap, trusty La Sportiva Mutant shoes, an Ultimate Direction Utility Belt around my waist in which I carried a water filter with 500ml flask, gas station gummy candies for fuel, a 3oz La Sportiva Blizzard Windbreaker jacket, and a Garmin Mini inReach.

Day 4: Kings Peak, UT (13,528’–24mi/4400’)

Three days of hot, remote, and often slow, bumpy off-road pedaling brought me from Boulder to the Henry’s Fork trailhead at sunset in the Uintas. Upon stirring awake in my bivy the next morning, my legs felt impossibly tired and heavy for producing a hard effort, but:

A) based purely on distance and vert, I thought the reported roundtrip FKT of 4h34m on Kings was relatively soft, and

B) I knew my legs would only accumulate more fatigue as the trip wore on, so I figured this peak was my best chance for setting an FKT. I hoped to give it an honest go.

About 10 miles from the trailhead the approach run crested Gunsight Pass (11,900’) and I caught the first up-close view of my goal summit. Despite onsighting, I decided to cut straight across the high basin to make a bee-line up the final 1200’ summit slope of boulders and talus instead of taking the more circuitous, recommended route over to Anderson Pass. This probably cut off a half-mile or so in each direction, but I could see no reason to not take the most direct line.

I summited at 2:16:55 from the trailhead and after asking an innocent bystander to snap my photo, immediately started descending back the way I’d came. I was excited to be feeling good at altitude and to be on pace for breaking the record by a substantial amount. On the run out I worked to maintain sub-7min miles over the rocky but slightly downhill trail and made it back to the trailhead at 3:58:xx,16min faster than (unbeknownst to me then) Jason Dorais’ previous best time of 4:14.

I was somewhat concerned about the long bike ride ahead to get to Evanston, WY that night for a much-needed resupply, but I also wasn’t sure when (or if!) I’d ever have another opportunity to run hard on this mountain, so I had tried to give my best effort. Calculating and balancing my energy like this would be a major theme for the remaining two and a half weeks. Living in Colorado, I realized, had conditioned me to a comparatively crowded and civilized high mountain experience with short distances between resupply towns and well-frequented if not outright busy trails and summits. The remoteness that came to characterize this trip and the infrequency of towns along the way brought this realization into stark relief.

A lengthy soak in the creek afterward was my first bath of the trip and did wonder to revive my legs. However, while I was eating lunch there in the shade, a thick, brown haze of wildfire smoke blew in, obscuring the stunning alpine scenery and providing an eerie backdrop that would dominate the remainder of my trip. Unfortunately, forest fire smoke like this is the new reality in the American West.

Smoky air, slow roads, and +100F temps made for a challenging three-day, 435 mile transfer to the Tetons. When I woke up in my bivy sack at Lupine Meadows in Teton National Park on day eight, I knew it was gonna be a rough one. I was already exhausted.

Day 8: The Grand Teton, WY (13,775’–15mi/7500’)

The initial climb up to Garnet Canyon was ominous as lightning and thunder cracked unexpectedly at 7 am and the moody cloud ceiling started spitting rain and then graupel. Having already gained a few thousand feet of vertical, however, I was reluctant to give up and try again the next day; I gamely continued marching up to the guide’s camp at the Lower Saddle where I would have an unobstructed view to the west and any incoming weather. It didn’t look great when I got there, but it was no longer raining as consistently, so I decided to continue on up to the Upper Saddle, always with an eye and ear to the sky.

The Grand is a familiar and favorite mountain for me–I’d summited it six times previously–so while it was disappointing to be so tired and have questionable weather conditions on it, I didn’t feel like I was missing out on anything. The Owen-Spaulding route is the easiest passage to the summit of the Grand Teton, but it still involves several pitches of 5.4 scrambling–technical rock that I would also downclimb on the descent since I wasn’t carrying any conventional rock climbing equipment for rappelling. The Grand Teton massif is, to me, one of the most compelling areas for alpine scrambling in the Lower 48, but, unfortunately, this particular day’s weather and my rock-bottom energy levels weren’t conducive to anything beyond getting up and down the mountain with the least amount of effort.

I knew I needed to recover if I was going to be able to continue making forward progress on my trip–a calculation unique to my chosen mode of transportation–so I took the afternoon easy, lounging around Jenny Lake and bivying only 30 miles down the road. It was 285 miles of riding between the Grand Teton and Granite Peak in Montana, but I had two days to cover it and it was 85% paved meaning that the pedaling would be much more efficient than the largely dirt and gravel I’d been riding up to this point.

Day 11: Granite Peak, MT (12,807’--25mi/8300’)

Because of its technical scrambling and remote location, Granite Peak in Montana’s Beartooth Range is touted as one of the most difficult state high points–maybe the most difficult in the Lower 48, right up there with Gannett and Washington’s Mt. Rainier. Granite was the biggest unknown mountain for me coming into this trip. Picking between the East Rosebud, West Rosebud, and Aero Lakes approaches seemed confusing. The consistent thing was that each route was long–25-26 miles no matter what–with a lot of off-trail travel. I ultimately chose East Rosebud because it was the closest access to the town of Red Lodge and because the Aero Lakes approach from Cooke City sounded complicated and with less precedent.

After a lovely 90min/4000’ approach run up Phantom Creek, the route gains Froze-to-Death Plateau–an above-treeline plain that spans approximately five miles and 2000’ of vertical gain across which efficient navigation is difficult. The footing is tricky talus, boulders, and tundra and the lack of orienting landmarks make it easy to stray off-route. Also, it’s very exposed to any fast-developing weather systems. I had good energy in my legs, however, and the skies were clear, so I was confident in being able to negotiate it without problems.

I paced myself across the plateau, cheating a bit by regularly consulting an offline map on my phone to make sure I was taking as direct a line as possible to the final saddle below the summit of Granite itself. At this point, I was still confident in besting the ascent FKT of 3h24 from the East Rosebud TH, but the final few hundred feet of scrambling are complex and inobvious, making the easiest, most efficient route difficult to discern. I often strayed into 5th-Class terrain, but eventually topped out at 3:29:50. I’d passed a single party of two who were roped up for the technical terrain, but other than that I hadn’t seen a single human since the trailhead. This summit felt Out There.

The run down was an extended, lackadaisical bumble. I was mostly motivated only by the thoughts of pizza and beer back in Red Lodge. The lack of effort I put into re-crossing Froze-to-Death Plateau, though, meant that I had plenty of energy left for the final seven miles of trail down Phantom Creek, so I was able to finish strongly, even in the midday heat.

Granite is an impressive and beautiful peak that doesn’t give up its grandeur easily. If it weren’t so deep in the backcountry and guarded by such a weather-exposed plateau I think it would be an instant classic for alpine rock climbing and general peakbagging. Unfortunately– or fortunately, depending on your perspective–it’s not easy to get back there. I think that’s okay, but I don’t see myself returning any time soon.

Twenty-five miles is a long run however you cut it, and after the 34 miles of mostly slow, loose gravel to get back to town I quickly scuttled any previous plans of riding still more that evening and instead treated myself to a giant pie and the only beer of the whole trip at the local pizza pub. There weren’t very many soft evenings on this trip, but with a full belly and the easy shelter of the local baseball dugout, this was definitely one of them.

Day 14: Cloud Peak, WY (13,166’–23mi/5600’)

I held guarded hopes for challenging the FKT on Cloud. However, while in Red Lodge a heat wave rolled into the center of the state and my 220 mile bike transfer from Granite was a couple of exhausting, somewhat stressful days of temperatures over +100F. Not ideal. Not to mention my 6h44min/8000’ run on Granite just a couple of days before. On yet another long, rolling, gradually uphill, backcountry approach I was already six minutes off the pace after the first hour of running. Upon crossing Paint Rock Creek, however, the terrain switched from idyllic, runnable, singletrack through wildflower-strewn meadows to an off-trail uphill grind, scrambling across talus and boulders. I was able to gain a couple of minutes back through here and reached the summit four minutes behind the FKT pace.

Once at the summit, however, any thought of flipping around and blasting the descent went away as I was distracted by the alpine splendor of Cloud’s glaciated eastern cirque and the dramatic alpine rock ridgeline of Mount Woolsey, the Merlon, and Black Tooth. What a place! I suddenly felt silly for my peakbagging mindset of running up to the highest point in the region when perhaps what I really should have been investigating was the alpine scrambling opportunities in this craggy zone to the north. Alas, it was my first visit to the area and I would probably have wanted a partner, rack, and rope for any technical onsighting anyways. Being committed to the bike and going truly fast and light can have its own limitations.

On the run back out I could feel the day heating up, so I filtered water many times and generally took it easy. Bombing the 25 miles down Tensleep Canyon on my bicycle felt like descending into a blast oven inferno. Temperatures would soar to +105F in town that day and after my 23 mile morning of foot travel I spent much of the afternoon sheltered in air conditioning before pedaling 35mi to the next town over, trying to get a jump on my transfer to the Wind River Range.

Day 17: Gannett Peak, WY (13,807’–38mi/8900’)

I had run Gannett once before, nine years prior. In my opinion, it’s a big intimidating outing–38miles roundtrip from the Green River Lakes trailhead, 14miles of that being off-trail across wild boulder fields, talus, and scree. The whole tour, the ascent of Gannett was in the back of my mind as the true crux–both for its arduous nature as a one-day effort and for the negative consequences it might have on my problematic achilles tendon.

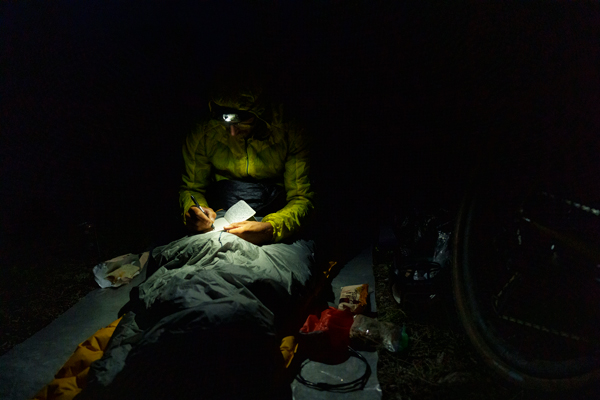

Just getting to the trailhead had been quite the punt. A 160-mile day across the center of the state to my sister’s house in Dubois was followed by 70 miles of bumpy gravel traversing the Wind River Range via Union Pass. It was one of the lowest mileage days of the entire trip, but I still felt beat up as I crawled into my sleeping bag the night before.

In 2012 I had established an FKT for Gannett that had held until just last year, when it was broken by only a few minutes. A small part of me was hoping that my legs would have the juice to attempt reclaiming the crown. As such, on the 12 mile flat approach run up the Green River valley I kept my foot on the gas, trying to move quickly while still pacing myself for what would inevitably be a very long day.

I covered this section well–7min faster than during my record run a decade earlier–but then found the crossing of the Green River to be much deeper than I’d remembered. From there the bushwhacky, off-trail rock hopping that defines the Tourist Creek route truly commences and I just did the best I could, reaching the Tourist-Wells Creek divide at exactly the same time as in 2012. The most direct line below Gannett’s western aspect requires crossing a portion of the Minor Glacier–a little intimidating in only running shoes–but it went fine and I was soon scrambling up the final 1500’ of Gannett itself.

From the glacier, it’s choose-your-own-adventure to the summit, the easiest route being a hideously loose scree gully. I soon became disgusted with this, however, and instead quested up a climber’s right, low-5th class spine of relatively solid rock, fingers crossed that I wouldn’t reach an impasse I was uncomfortable onsight soloing. Ultimately, this choice was certainly more fun but probably a bit slower, and I popped out on the summit at 4:49, about 3min behind my split from nine years ago.

There was a guided party on the summit who had ascended the much more popular Bonney Pass/Gooseneck Glacier route, and I had them hastily snap my photo before beginning the descent. The skies had been heavy and gloomy all morning, providing ideally cool temps, but they now seemed to be threatening precipitation.

Sure enough, a few minutes after starting down it began sprinkling benignly, so I didn’t give it much thought, but then a couple miles of rock-hopping later–below the western slopes of Mt Solitude–the skies opened up in earnest. Dang it. I didn’t care about getting wet, but now all of the boulders that I was hopping across were saturated and slippery, making for truly treacherous footing. At first I thought I could push on at FKT intensity, but after a few slips I finally made a mistake with consequences. My foot inevitably skated on a patch of lichen and in catching myself I incurred a deep gash on my shin and painfully strained my right rotator cuff.

The FKT attempt was officially off. I just couldn’t risk falling again in this jumble of refrigerator-, car-, and house-sized boulders, especially while so deep in the backcountry. Thankfully, my shin clotted quickly, but my shoulder was nearly useless as I tentatively gimped my way back down Tourist Creek to re-wade the Green River and run the 12 miles of trail back out to the trailhead. Without the focus and purpose of chasing a record the run out became an interminable grind. I ran out of food and water, of course, and seriously questioned any silly notions I’d held about possibly running the Leadville 100 the following month. Running felt miserable.

Finally, back at my bicycle, I surmised that once a decade was just about right for Gannett. The Wind River Range is a devastatingly beautiful zone, but I don’t feel the need to do Gannett-in-a-day again anytime soon. Except for maybe on skis. The mental crux of the day came after I’d washed the trail dust off in the lake. I was exhausted from the Gannett outing, but I was also nearly out of food. All I wanted to do was lay down in my bivy and go to sleep, but I knew I couldn’t responsibly do so with the meager calories I had. Instead, I got on my bike and pedaled 50 long miles out to Pinedale, where I was able to re-stock at a grocery store just before it closed and wake up to a glorious café breakfast the next morning.

Longs Peak (14,255’–10mi/5000’)

After Gannett, I had a four-day, 550mi bike ride back home to Colorado. This was nice to let my battered body recover a little before my last run, up and down the backyard peak. Even if it weren’t the closest 14er to Boulder, I would consider Longs the best 14er in the state. It’s a truly technical mountain with no real walk-up option on it, and its northeast face–the venerable Diamond–is the highest quality alpine big wall in the country. I’ve summited Longs 92 times and can’t wait for the next 92. Every summit feels like a gift and a privilege.

On the last morning of the trip, I rode my bike over the 12,000’ Continental Divide in Rocky Mountain National Park via Trail Ridge Road. A quick lunch in Estes Park saw me leaving the Longs Peak trailhead at 2:30 pm–a decidedly unconventional time for your average ascensionist. The forecast looked good, though, and I was buzzing on caffeine and last-day adrenaline. I felt so good, in fact, on the run-up to treeline that I spontaneously decided to climb the Kieners Route on Longs’ vertiginous east face rather than the shorter, but-still-5th-Class Cables Route on the north face.

Kieners is a long, classic 5.4 scramble that is accessed by traversing the spectacular Broadway Ledge before flirting with the edge of the Diamond via a series of moderate chimneys and cracks. It’s my favorite way up the mountain, and since I hadn’t yet climbed it this summer, I figured no time was better than the present. Once across the snowy and icy Lambslide couloir, the conditions were perfect. I took it easy, simply enjoying the movement and wild position as I punctuated such a long trip in one of my favorite places. After downclimbing the Cables and running back down to my bike at the trailhead, the 45 miles, largely downhill bike home to Boulder felt like a familiar cooldown.

- - -

Completing this ambitious trip impressed upon me the quizzical paradox that I find to be at the heart of all of my most rewarding adventures. The difficult moments stacked up one after another until discomfort and hardship become almost routine. In this accretion, however, I become struck simultaneously with the knowledge that I can endure so much more than I originally thought, but that I am also an infinitesimal speck of nothingness in the face of the mountains’ imperturbable and imposing indifference. I am strong and I am weak. I am so much more capable than I thought, and yet I am more aware than ever of my need for other’s support. A multi-sport tour like this one is the most reliable context I’ve found for experiencing and exploring that paradox. The running and scrambling allow me to keep it simple and stay off the beaten path. The bike facilitates a multi-day or multi-week immersion without unduly beating up my body. I’m looking forward to more of them.